The Winter Show and the Comfort of Beautiful Things

A sculptural flower pendant shown in a Larry Rivers–focused presentation, part of the broader mid-to-late 20th century movement where artists treated jewelry as wearable art. Presented by Didier Ltd.

The Winter Show is both a celebration of design and a mission-driven event. Since 1954, the fair has raised funds for the East Side House Settlement, supporting education and workforce development programs in the Bronx. Along with uplifting underserved communities, it also stirs something in attendees— a sense of comfort in the presence of beautiful things. With over 70 renowned international dealers, the show features rare antiques, jewelry, and collectible art and design objects meant to inspire reverence for craft, history, and meaning.

With this in mind, objects feel desirable, not just for their rarity or beauty, but because they carry an emotional narrative we identify with. Beautiful things often act as emotional containers, holding memory, identity, and a sense of continuity. In psychology, we refer to these as transitional objects. Typically used to describe soothing objects children use to manage separation and security, compelling designs can offer a similar sense of security. In this way, beauty regulates us, especially during moments of stress. This helps explain why the objects we curate often reveal something about us. It’s curation as identity-making.

So many objects at this year’s Winter Show offered the kind of beauty we want to surround ourselves with. Here are a few that stood out.

Grete Jalk Chair, Model 9-1, circa 1963; Manufactured by Paul Jeppesen, St. Heddinge, Denmark, Oak-veneered plywood. Presented by Graf, Kaplan & Zemaitis

1. Grete Jalk Chair, circa 1963.

Jalk designed this piece around a single ribbon-like curve in motion, drawing from classical ornamentation but translating it into a continuous structural curve. The chair feels historically familiar yet modern, an example of how objects can carry echoes of tradition, acting as a kind of emotional bridge. By shaping something new from what feels familiar, the piece reminds us we can evolve while still holding onto what feels secure.

Venetian Glass Objects, Various Makers (1920–1960). Presented by Glass Past.

2. Venetian Glass Objects

Murano glass has historically been one of Venice’s most celebrated traditions, and in the early 20th century, it entered a new era of revival and experimentation.

Beginning in the 1920s Venetian glass was influenced by the Art Deco movement, embracing bold color, stylized geometry, and luxury objects in the forms of candlesticks, vases, and sculptures. These designs became symbols of refinement, rooted in old-world Venetian romance but designed for modern rooms.

During the next forty-year period, there was a lot of societal instability including the rise of Fascism in Italy, WW II, and economic uncertainty. And luxury, decorative objects offered an antidote— escapism. Often when the world feels unstable, people seek beauty, craftsmanship, and ritual as a type of relief. After WWII, Murano glass became part of Italy’s cultural re-emergence, reflecting both innovation and tradition. These objects evolved to be a part of modern Italian identity, transforming a centuries-old technique into high design.

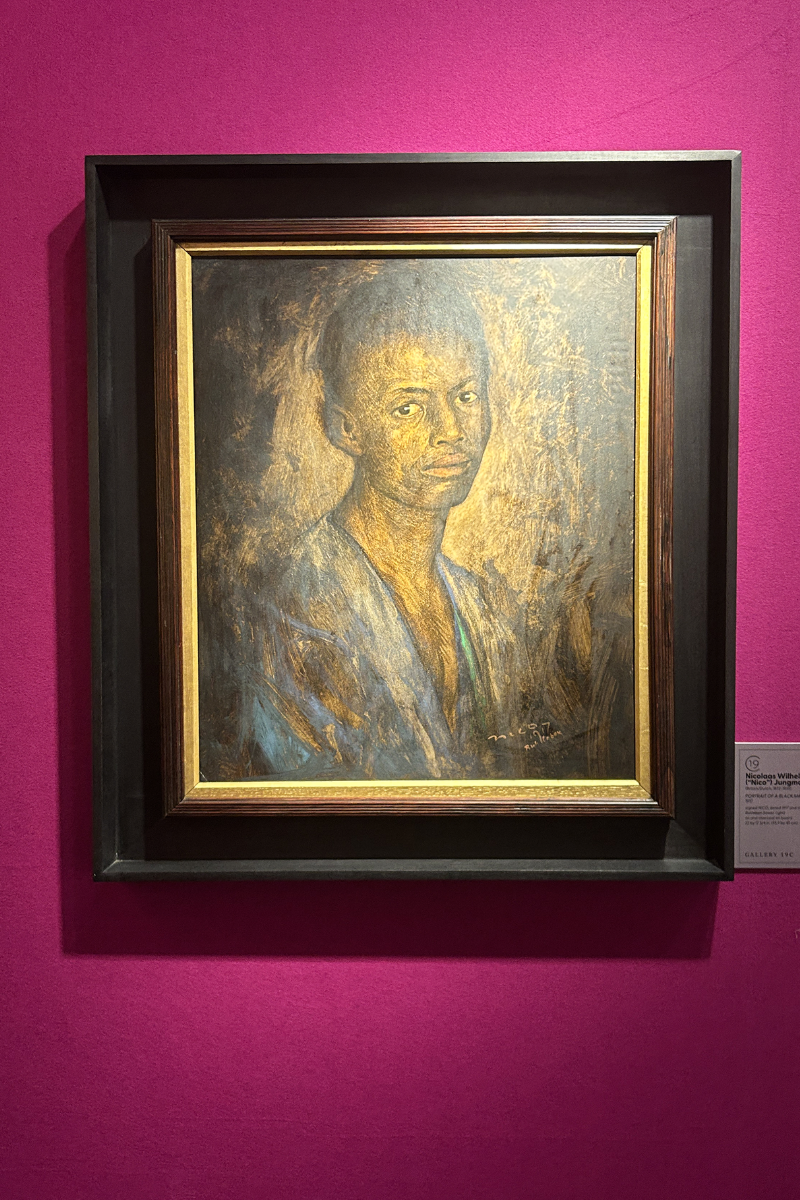

Nicolaas Wilhelm (“Nico”) Jungmann; Portrait of a Black Man, 1917, inscribed Ruhleben. Presented by Gallery 19C

3. Portrait of a Black Man, 1917

Jungmann, a Dutch-born artist working in Britain, painted this portrait at Ruhleben, a civilian internment camp in Germany during World War I. Such camps confined civilians deemed “enemy nationals,” holding them for years under wartime suspicion. Yet despite the hardship, there was a remarkable cultural life inside the camps, including concerts, lectures, and art-making. This portrait emerges from this setting of confinement, where displacement and efforts to strip people of identity were met with human endurance.

The composition is pared back with no lavish interior or props, just a gaze and quiet presence. In 20th-century European art, Black subjects were often exoticized figures or reduced to colonial symbols. Here, the portrayal feels intimate and humanizing, underscoring how simple presence can become a form of resistance. It’s identity made visible, and a reminder of the emotional weight images can carry.

Louise Nevelson Necklace 1965; painted black with citrine-like chips and gold highlights. Presented by Didier Ltd.

4. Nevelson black Sculptural Necklace

Louise Nevelson, one of the most prominent American sculptors of the 20th century, was known for her black wall assemblages made of found wood fragments, architectural remnants, and layered geometric shadow-box forms. Her work is associated with abstraction, urban materiality, and black as a way of drawing attention to form. This necklace is essentially her sculpture miniaturized for the body.

In the mid-1960s, the boundaries between fine art, design, and jewelry were collapsing and artists were experimenting with jewelry as an art form. Psychologically, black unifies chaos, and in absorbing light, it creates a sense of containment. The gold highlights add small glints, like city lights in the dark. Overall, the piece feels restrained yet bold, giving the body structure and groundedness. In this way, adornment becomes self-definition, intended to create structure and occupy space as an assertion of identity.

Art Deco furnishings, including a sculptural English Art Deco “Cloud” chair by Lou Epstein, alongside a pair of French Art Deco chairs by Maison Levitan. Presented by Milord Antiquités.

While these objects may serve different aesthetic sensibilities, they all evoke meaning that supports identity and wellbeing. They are proof that someone noticed, cared, and preserved. In this way, beauty acts as an anchor, supporting our evolving selves in the face of change, stress, and even societal upheaval. What pieces have you found beautiful and comforting? Share in the comments.

Written by Sarah Seung-McFarland

Sarah Seung-McFarland, Ph.D., is a licensed psychologist with a specialty in fashion and design psychology, and founder of Trulery.